Code

# source the functions provided in part 1

source("https://github.com/xuyiqing/lalonde/blob/main/tutorial/functions.R?raw=TRUE")In this section, We report findings using the LaLonde female samples reconstructed by Calónico and Smith (2017), referred to as the LaLonde-Calónico-Smith (LCS) sample.

Consistent with LaLonde’s original analysis, the outcome variable is earnings in 1979 (re79). We use the same set of covariates as in LaLonde. Notably, this set does not include two pretreatment variables: earnings in 1974 and employment status in 1974. We also exclude the number of children in 1975 (nchildren75), which is available in the LCS dataset, from the covariates so that it can serve as a placebo outcome.

# source the functions provided in part 1

source("https://github.com/xuyiqing/lalonde/blob/main/tutorial/functions.R?raw=TRUE")load("data/lcs.RData")

# expc = 0: experimental treated;

# expc = 1: experimental control;

# expc = 2: psid control.

lcs_psid$expc <- 0

lcs_psid[lcs_psid$treat==0, ]$expc <- 2

lcs_tr <- lcs[lcs$treat==1, ]

lcs_co <- lcs[lcs$treat==0, ]

lcs_co$treat <- 1

lcs_co$expc <- 1

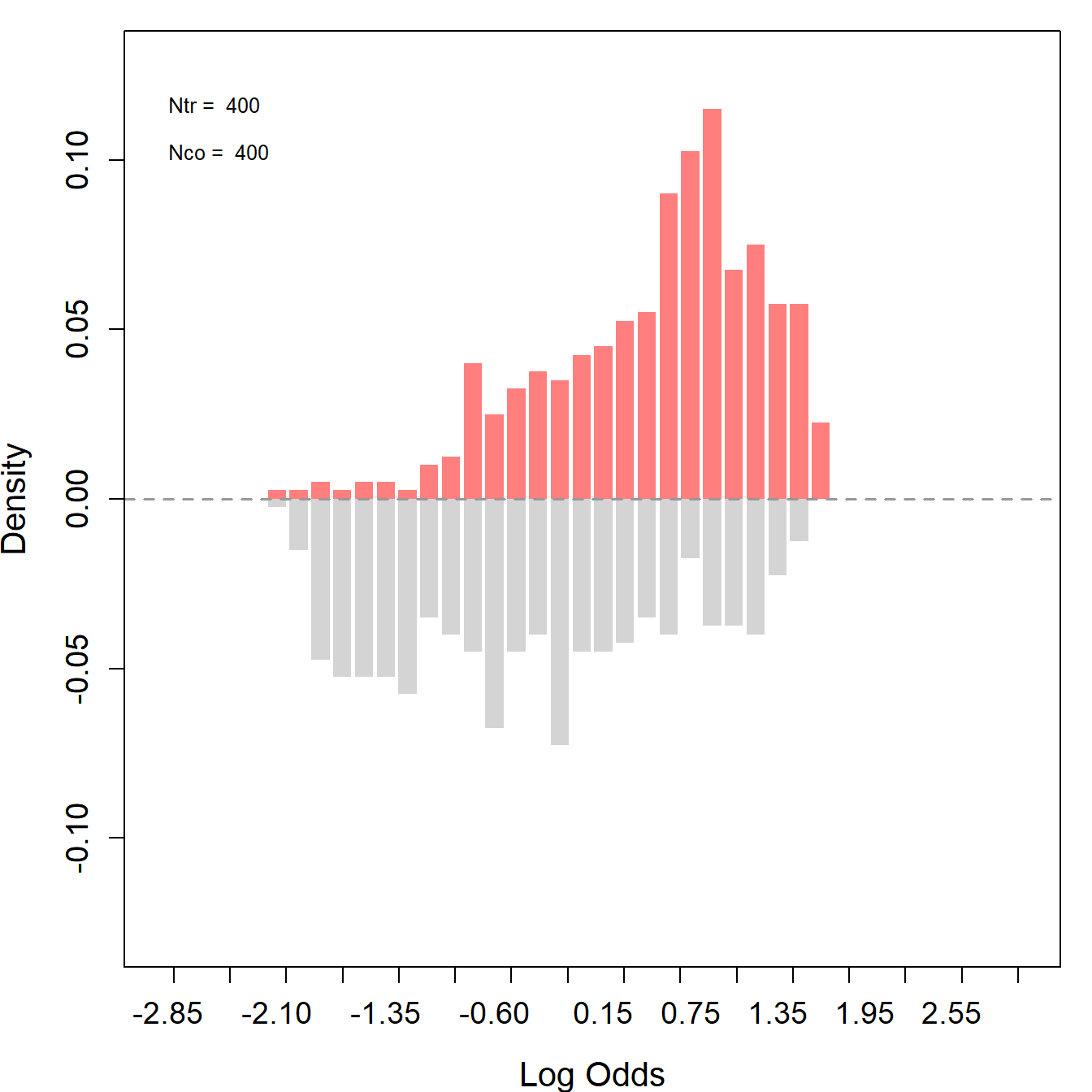

lcs_psid.plus <- rbind.data.frame(lcs_psid, lcs_co)We assess overlap in covariate distributions between treated and control groups based on the propensity score via GRF (log odds ratio) for the LCS-Experimental and LCS-PSID data.

# define variables

Y <- "re79"

treat <- "treat"

# redifine covariates: removing "nchildren75" to be used as placebo outcome

covar <- c("age", "educ", "nodegree", "married", "black", "hisp", "re75", "u75")Figure B10 demonstrates overlap in the LDW using the propensity score estimated via GRF (log odds ratio).

We then trim the data to improve overlap in covariate distributions by removing units with poor overlap based on the propensity score. This step aims to refine the datasets to improve later causal inference. With the trimmed data, we can reassess overlap for each group.

Like before, we start by assessing overlaps between the distributions of the treated and control groups based on log-odds derived from propensity scores.

lcs_psid.plus_ps <- assess_overlap(data = lcs_psid.plus, treat = treat, cov = covar, xlim = c(-15, 5))Then, we proceed with trimming to improve the quality of the causal inference. After trimming, we would expect the distributions to align more closely - the treatment and control groups are more comparable according to their covariates.

trim <- function(data, ps = "ps_assoverlap", threshold = 0.9) {

sub <- data[which(data[, ps] < threshold), ]

return(sub)

}

#Trim

lcs_psid_trim <- trim(lcs_psid.plus_ps, threshold = 0.9)

# psid data: excluding the experimental controls

lcs_psid_trim_match <- subset(lcs_psid_trim, expc %in% c(0, 2) & ps_assoverlap)

# re-estimate propensity scores and employ 1:1 matching

lcs_psid_trim_match <- psmatch(data = lcs_psid_trim_match, Y = "re79", treat = "treat", cov = covar)The propensity scores are reestimated after trimming.The plots below show good overlaps especially in the center, indicating an improved balance and common support between the treated and control groups. The before-after trimming comparison suggests that the trim effectively removes units that were less comparable.

# psid data

lcs_psid_trim_match_ps <- assess_overlap(data = lcs_psid_trim_match, treat = treat, cov = covar, xlim = c(-3,3), breaks = 40)

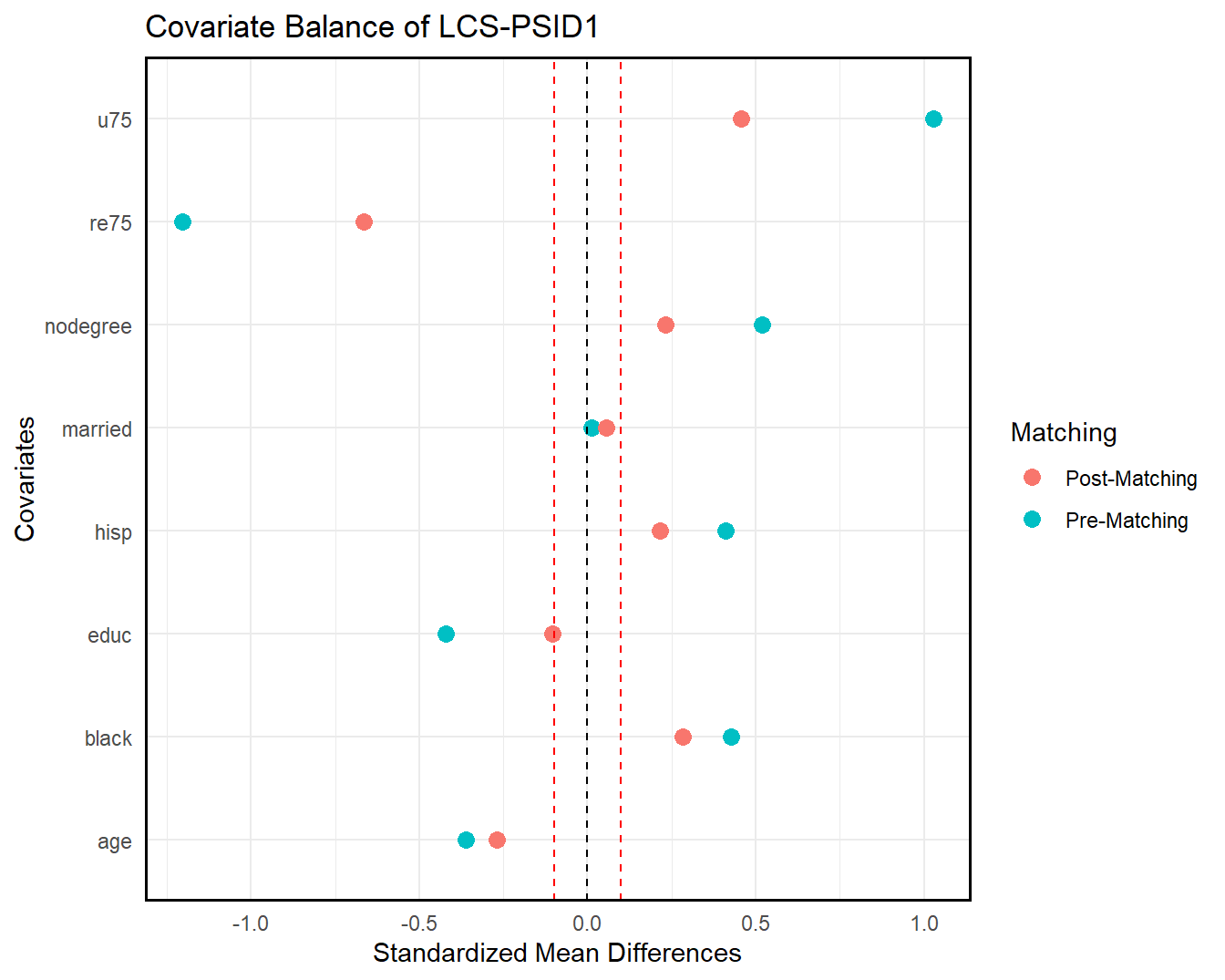

We can also check covariate balance directly by love.plot().

load("data/lcs.RData")

# psid data

love.plot(lcs_psid, lcs_psid_trim_match, treat = treat, covar = covar, title = "Covariate Balance of LCS-PSID1")

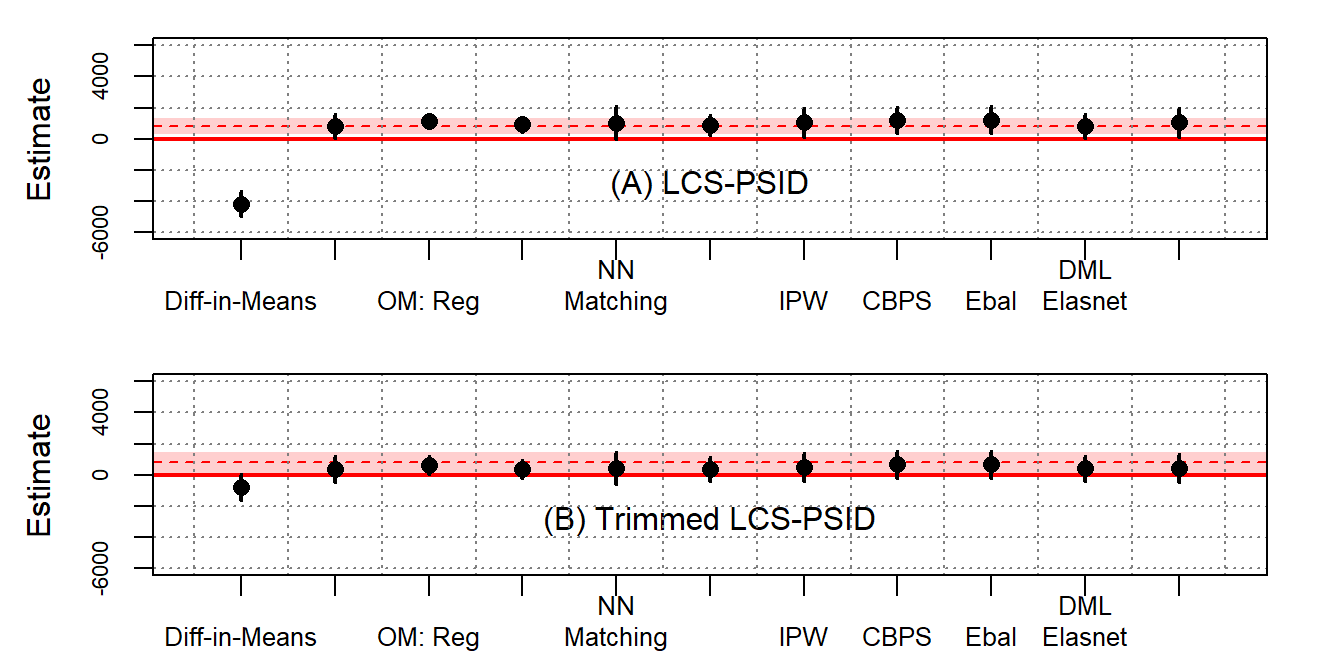

Table B6 shows the ATT estimates using the reconstructed LaLonde female samples. Reconstructed PSID-1 is used as the nonexperimental control group. Figure B11 visualizes the ATT estimates.

Using the LCS female samples, we find that many modern methods yield estimates close to the experimental benchmarks, though standard errors are often quite large.

# print the result

a <- list(out3, out4)

# columns are samples

n <- nrow(out1) + 1 # add experimental benchmark

sav <- matrix("", n, length(a)*3-1)

for (j in 1:length(a)) {

out <- a[[j]]

for (i in 1: (n-1)) {

sav[i+1, j*3-2] <- sprintf("%.0f", out[i, 1])

sav[i+1, j*3-1] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.0f", out[i, 2]), ")")

}

}

sav[1, 1] <- sprintf("%.0f", out1[1, 1]) # full experimental

sav[1, 4] <- sprintf("%.0f", out2[1, 1]) # trimmed experimental (PSID)

sav[1, 2] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.0f", out1[1, 2]), ")")

sav[1, 5] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.0f", out2[1, 2]), ")")

colnames(sav) <- c("LCS-PSID", "", "", "LCS-PSID (PS Trimmed)", "")

rownames(sav) <- c("Experimental Benchmark", "Difference-in-Means", "Regression", " Oaxaca Blinder", "GRF", "NN Matching", "PS Matching", "IPW", "CBPS", "Entropy Balancing", "DML-ElasticNet", "AIPW-GRF")

sav %>% knitr::kable(booktabs=TRUE, caption = "TABLE B6 in the Supplementary Materials (SM), ATT Estimates: Reconstructed LaLonde Female Samples")| LCS-PSID | LCS-PSID (PS Trimmed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Benchmark | 821 | (308) | 785 | (380) | |

| Difference-in-Means | -4172 | (412) | -804 | (422) | |

| Regression | 808 | (389) | 359 | (414) | |

| Oaxaca Blinder | 1128 | (239) | 608 | (296) | |

| GRF | 918 | (238) | 395 | (296) | |

| NN Matching | 1037 | (531) | 443 | (519) | |

| PS Matching | 872 | (333) | 364 | (402) | |

| IPW | 1043 | (468) | 506 | (459) | |

| CBPS | 1217 | (429) | 670 | (435) | |

| Entropy Balancing | 1229 | (430) | 673 | (436) | |

| DML-ElasticNet | 814 | (388) | 411 | (410) | |

| AIPW-GRF | 1050 | (487) | 424 | (460) |

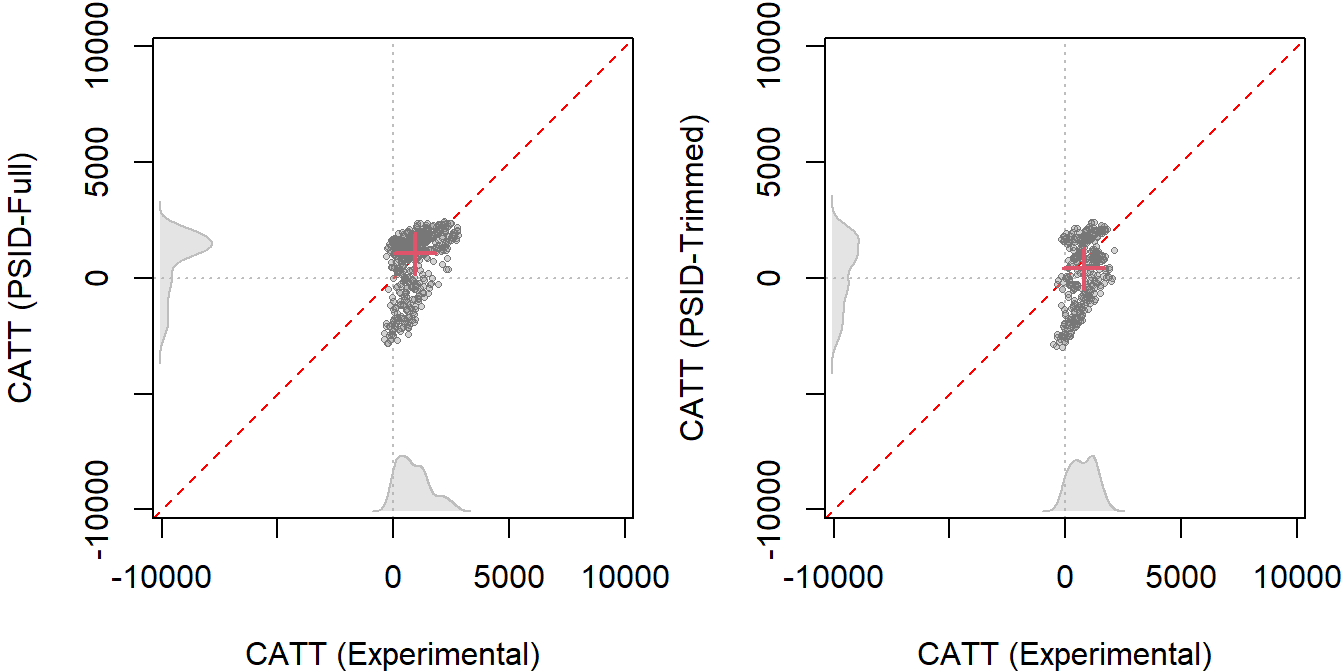

The figures below show the CATT estimates using the reconstructed LaLonde female samples.

Each point on the scatter plots represents a pair of CATT estimates for a single unit: one from the experimental benchmark and one from the observational method. Points that lie on the 45-degree line (the red line) are cases where the observational and experimental methods yield the same estimate.

# estimate catt

catt.lcs <- catt(lcs, Y, treat, covar)

catt.lcs.psid <- catt(lcs_trim_psid, Y, treat, covar) # trimmed experimental data

catt.psid <- catt(lcs_psid, Y, treat, covar)

catt.psid.trim <- catt(lcs_psid_trim, Y, treat, covar)par(mfrow = c(1,2))

# plot catt - "CATT (Experimental)" and "CATT (PSID-Full)"

par(mar = c(4, 4, 1, 1))

catt1 <- catt.lcs$catt

att1 <- catt.lcs$att[1]

catt2 <- catt.psid$catt

att2 <- catt.psid$att[1]

plot_catt(catt1, catt2, att1, att2, "CATT (Experimental)", "CATT (PSID-Full)",

main = "", c(-8000, 8000))

# plot catt - "CATT (Experimental)" and "CATT (PSID-Trimmed)"

par(mar = c(4, 4, 1, 1))

catt1 <- catt.lcs.psid$catt

att1 <- catt.lcs.psid$att[1]

catt2 <- catt.psid.trim$catt

att2 <- catt.psid.trim$att[1]

plot_catt(catt1, catt2, att1, att2, "CATT (Experimental)", "CATT (PSID-Trimmed)",

main = "", c(-8000, 8000))

Note: Scatterplots show the CATT using both experimental data (x-axis) and nonexperimental data (y-axis) from the reconstructed LaLonde female samples. Each dot corresponds to a CATT estimate based on the covariate values of a treated unit, while each red cross symbolizes the ATT estimates. For every estimate, the AIPW estimator is employed, with the GRF approach for estimating nuisance parameters. Different subfigures indicate various data comparisons: Subfigure A: Compares LCS-Experimental with LaLonde-PSID1. Subfigure B: Compares Trimmed LCS-Experimental to Trimmed LCS-PSID.

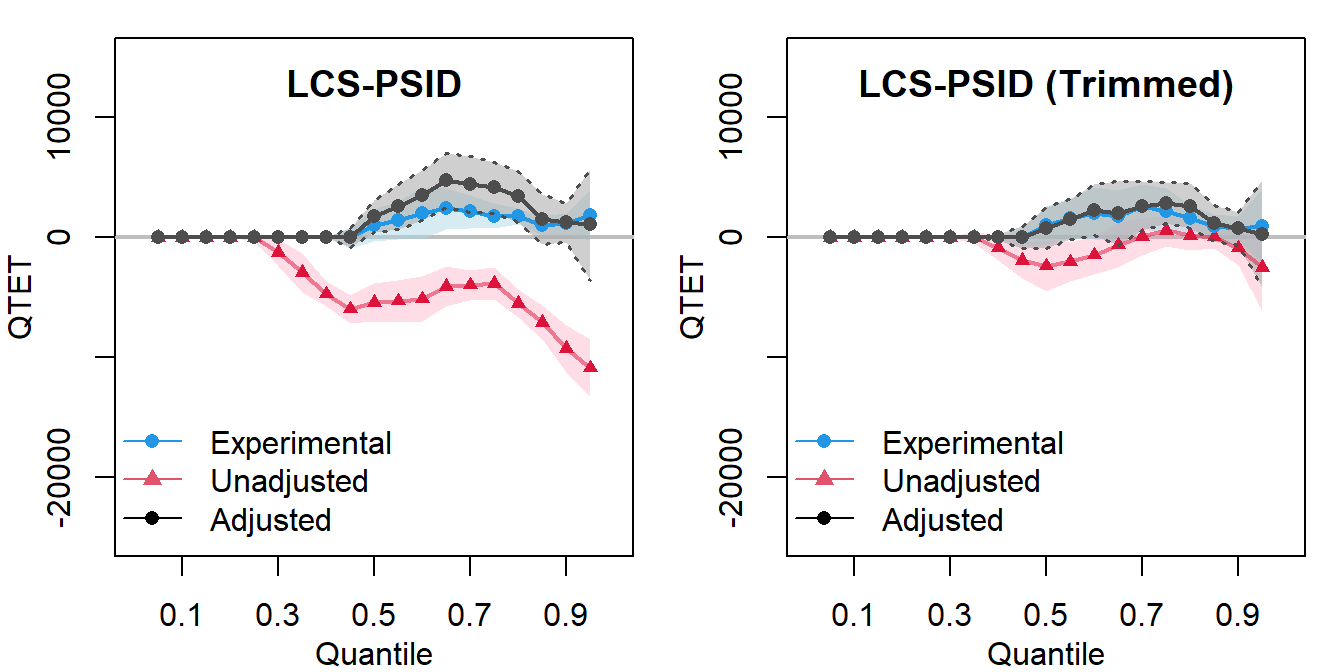

The Figures below show the quantile treatment effects on the treated in reconstructed LaLonde female samples. QTET analysis helps us to see where along the outcome distribution the treatment is more or less effective.

# estimate qte (some of the following lines are not run due to computational limitation)

## experimental

qte.lcs <- est_qte(Y, treat, NULL, data = lcs)

qte.lcs.psid <- est_qte(Y, treat, NULL, data = lcs_trim_psid)

## non-experimental

qte.lcs_psid <- est_qte(Y, treat, covar, data = lcs_psid) # adjusted

qte.lcs_psid0 <- est_qte(Y, treat, NULL, data = lcs_psid) # unadjusted

qte.lcs_psid.trim <- est_qte(Y, treat, covar, data = lcs_psid_trim) # adjusted

qte.lcs_psid.trim0 <- est_qte(Y, treat, NULL, data = lcs_psid_trim) # unadjusted# plot qte

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

# PSID

plot_qte(qte.lcs_psid, qte.lcs_psid0, qte.lcs, main = "LCS-PSID", ylim = c(-25000, 15000))

legend("bottomleft", legend = c("Experimental", "Unadjusted", "Adjusted"),

lty = 1, pch = c(16, 17, 16), col = c(4, 2, 1), bty = "n")

# PSID trimmed

plot_qte(qte.lcs_psid.trim, qte.lcs_psid.trim0, qte.lcs.psid, main = "LCS-PSID (Trimmed)", ylim = c(-25000, 15000))

legend("bottomleft", legend = c("Experimental", "Unadjusted", "Adjusted"),

lty = 1, pch = c(16, 17, 16), col = c(4, 2, 1), bty = "n")

Note: Figures show the quantile treatment effects on the treated (QTET) using the reconstructed LaLonde female samples. Results from the experimental data are shown in blue and results from the nonexperimental data are shown in red for raw estimates and black for covariate-adjusted estimates. Each dot corresponds to a QTET estimate at a particular quantile, while shaded areas represent bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Unadjusted models do not incorporate covariates while adjustment models use the full set of covariates to estimate the propensity scores with a logit.

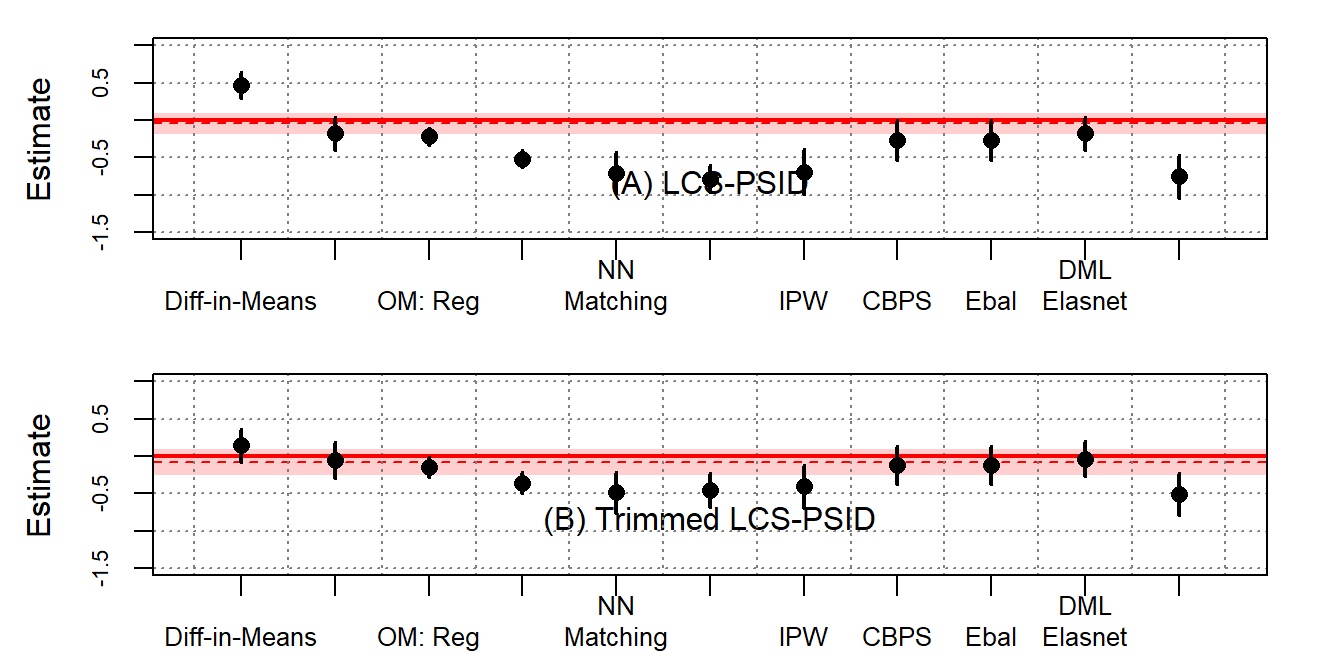

We conduct placebo analyses to further assess the plausibility of unconfoundedness. In the placebo analysis, estimators using observational data usually generate negative estimates. we fail to substantiate the unconfoundedness assumption with a placebo test using the number of children in 1975, a variable absent in LaLonde, as the placebo outcome.

Y <- "nchildren75"

treat <- "treat"

covar <- c("age", "educ", "nodegree", "married", "black", "hisp", "re75", "u75")

set.seed(1234)

# experimental

out1 <- estimate_all(lcs, Y, "treat", covar)

out2 <- estimate_all(lcs_trim_psid, Y, "treat", covar)

# no experimental

out3 <- estimate_all(lcs_psid, Y, "treat", covar)

out4 <- estimate_all(lcs_psid_trim, Y, "treat", covar)# print the result

a <- list(out3, out4)

# columns are samples

n <- nrow(out1) + 1 # add experimental benchmark

sav <- matrix("", n, length(a)*3-1)

for (j in 1:length(a)) {

out <- a[[j]]

for (i in 1: (n-1)) {

sav[i+1, j*3-2] <- sprintf("%.2f", out[i, 1])

sav[i+1, j*3-1] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.2f", out[i, 2]), ")")

}

}

sav[1, 1] <- sprintf("%.2f", out1[1, 1]) # full experimental

sav[1, 4] <- sprintf("%.2f", out2[1, 1]) # trimmed experimental (PSID)

sav[1, 2] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.2f", out1[1, 2]), ")")

sav[1, 5] <- paste0("(", sprintf("%.2f", out2[1, 2]), ")")

colnames(sav) <- c("LCS-PSID", "", "", "LCS-PSID (PS Trimmed)", "")

rownames(sav) <- c("Experimental Benchmark", "Difference-in-Means", "Regression", " Oaxaca Blinder", "GRF", "NN Matching", "PS Matching", "IPW", "CBPS", "Entropy Balancing", "DML-ElasticNet", "AIPW-GRF")

sav %>% knitr::kable(booktabs=TRUE, caption = "TABLE B7 in the Supplementary Materials (SM): Placebo Test: Number of Children in 1975 as the Outcome")| LCS-PSID | LCS-PSID (PS Trimmed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Benchmark | -0.05 | (0.08) | -0.08 | (0.09) | |

| Difference-in-Means | 0.47 | (0.09) | 0.14 | (0.11) | |

| Regression | -0.18 | (0.11) | -0.05 | (0.12) | |

| Oaxaca Blinder | -0.22 | (0.06) | -0.15 | (0.07) | |

| GRF | -0.52 | (0.06) | -0.36 | (0.07) | |

| NN Matching | -0.71 | (0.14) | -0.49 | (0.14) | |

| PS Matching | -0.79 | (0.09) | -0.46 | (0.12) | |

| IPW | -0.69 | (0.15) | -0.41 | (0.15) | |

| CBPS | -0.27 | (0.14) | -0.12 | (0.13) | |

| Entropy Balancing | -0.27 | (0.14) | -0.12 | (0.13) | |

| DML-ElasticNet | -0.18 | (0.11) | -0.03 | (0.12) | |

| AIPW-GRF | -0.75 | (0.15) | -0.51 | (0.14) |

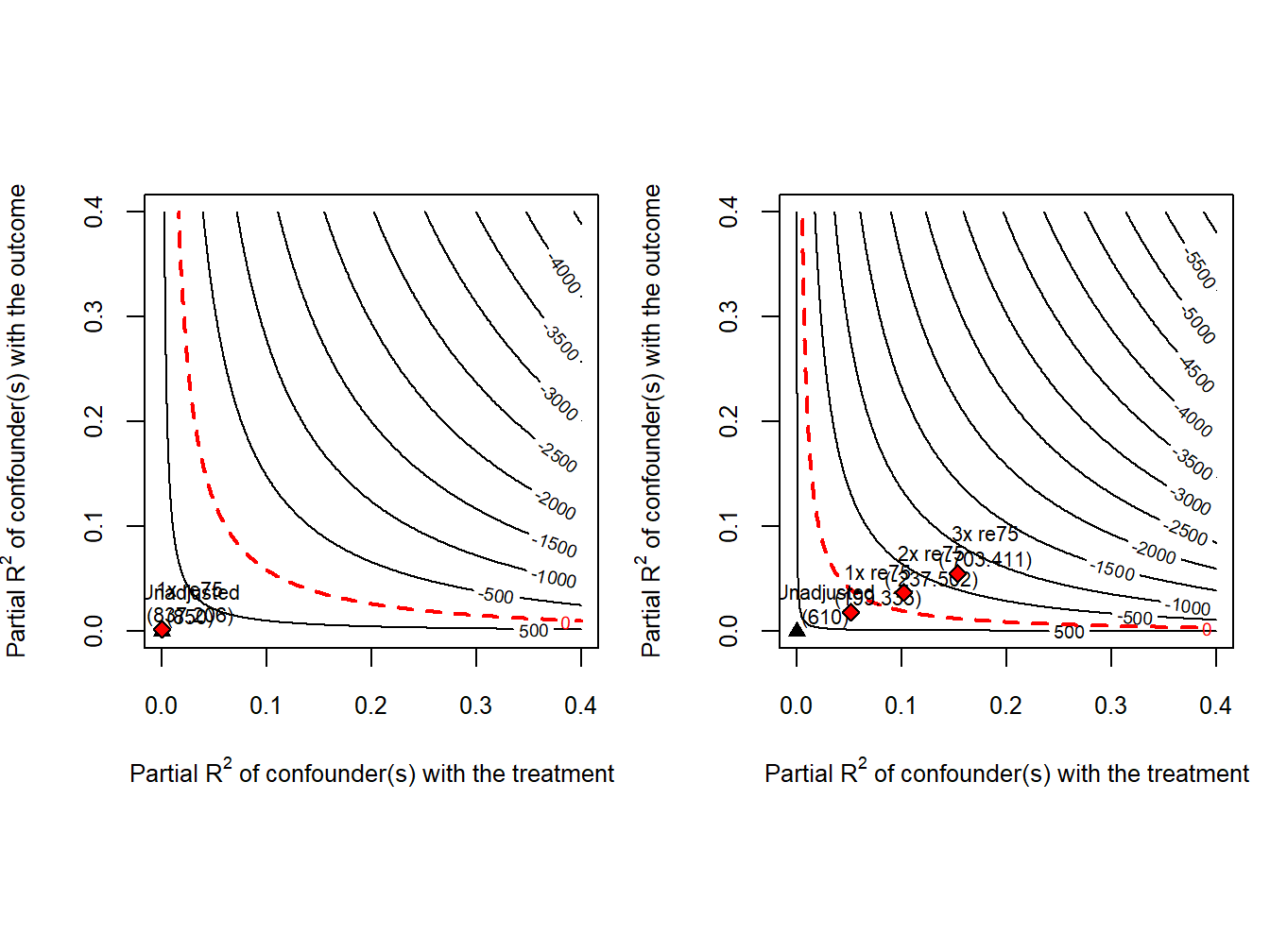

Below are our sensitivity analyses using the reconstructed LaLonde female samples, with results depicted in contour plots below.

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

# define variables

Y <- "re79"

treat <- "treat"

# redifine covariates: removing "nchildren75" to be used as placebo outcome

covar <- c("age", "educ", "nodegree", "married", "black", "hisp", "re75", "u75")

bm <- c("re75")

# LCS-Experimental data

sens_ana(lcs, Y, treat, covar, bm, kd = 1)

# trimmed LCS-PSID data

sens_ana(lcs_psid, Y, treat, covar, bm, kd = 1:3)

The analysis shows that the estimated training effect based on LCS-PSID is sensitive to potential confounders that behave like re75.